What a child can do in cooperation today, he can do alone tomorrow.

— Lev. S. Vygotsky

During my project in Colombia, I arrived with a familiar label: English teacher. I’d spent years in large language schools and was tired of the usual way of teaching. I wanted to do something more meaningful through the English language, something that involved bodies, stories, and imagination.

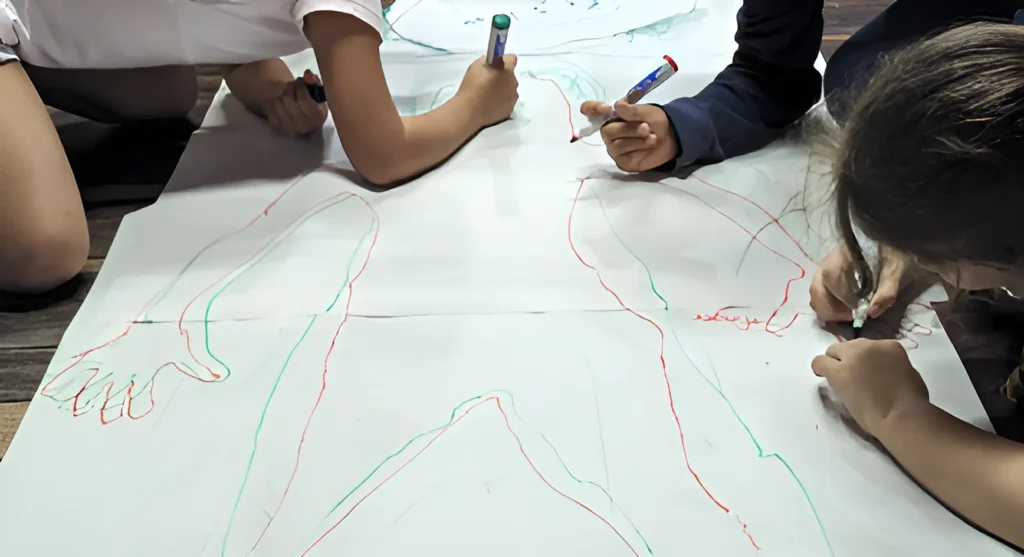

The project included children of different ages, but in this blog I focus on one group, aged six to eight. Their energy, curiosity, and willingness to play shaped how the sessions unfolded each day.

The first thing I noticed in Colombia was the noise, joyful, unstoppable noise.

The children in Fredonia came bursting through the door, chattering in Spanish, full of stories and energy. They didn’t want to sit in a circle; they wanted to dance in one. And so, I stopped trying to contain them.

Instead, I joined their flow, weaving English words into movement, using yoga as a bridge rather than a boundary. The body became a second language; movement, the grammar of understanding.

The Girl Who Liked Being “Mean”

One afternoon, a group of children gathered around me to complain that one of the girls was “mean.”

“She’s always mean,” they said.

“I’m mean because I like it.”, the girl shrugged, half-smiling

Before I could speak, another child turned to her and said: “You might like it, but others don’t.”

Then another added softly, “Nobody wants to be your friend if you’re mean.”

Silence fell.

We stayed with the pause that followed.

The language that emerged naturally led us to practise together as a group, using simple phrases such as “I’m sorry,” “I forgive you,” “Let’s be kind,” in English, as part of the shared language emerging from the moment.

What stayed with me was not a shift in behaviour, but how language, tone, and play created space for children to hear one another differently.

Learning Through Movement and Play

As the weeks went on, the children began inventing their own games.

They’d act them out in Spanish and gestures, and I’d gently introduce the English words: “jump,” “breathe,” “together,” “smile.” They learned English not by memorising, but by embodying. Their joy became the lesson plan.

Over time, children would insist on showing me yoga shapes during storytelling or play. As they moved, they began attaching words to the shapes, first individual words, then short chunks, and eventually simple phrases.

Parents later shared that the children would sometimes repeat English words at home when they recognised something familiar on TV, especially during cartoons, small traces of the sessions weaving into everyday life.

The Magic of Stillness

Stillness didn’t come easily.

The first time I dimmed the lights and invited them to breathe, they fidgeted, giggled, peeked under their scarves. They weren’t used to slowing down.

We used scarves, paper, and breath to play with air; to notice movement within stillness.

Through these playful and sensorial activities, children encountered moments of quiet in their own time, without being asked to hold or sustain them.

When the Village Joins In

By the final weeks, the project had expanded beyond the sessions themselves.

Parents helped organise excursions and contributed materials.

We spoke informally about taking activities outdoors: to the coffee farms, the hilltops, the sound of wind.

The children’s learning sat within a wider community rhythm, rather than being contained within the sessions alone.

Closing Reflection

In Fredonia, I observed how children’s energy shifted depending on the space offered to it. At first, I tried to contain it. Later, I realised that this energy was the starting point.

As children suggested games and shaped activities, it became clear that freedom worked best when it was held, not controlled. The children were learning English, while also learning how to move, listen, and share space together.

Facilitating in Fredonia reminded me that learning often begins in noise, movement, and play. When these are met with attention and responsiveness, they can open into moments of connection, creativity, and shared understanding.

The children found new words, and I was reminded that the most fluent language in the room was often joy.

*All project descriptions are anonymised and shared with consent where required. No participant-identifying information is included.